Mental health conditions often present differently in women because biology, social expectations, and lived experiences intersect in powerful ways. Hormonal shifts, reproductive events, caregiving roles, and exposure to gender‑based violence all influence how symptoms emerge and how they are interpreted by others.

Several overlapping factors shape women’s mental health:

- Hormonal changes across the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, postpartum, and menopause can affect mood, energy, sleep, and stress tolerance.

- Social expectations to “hold it all together” at work and at home can lead women to hide or minimize their distress.

- Higher rates of sexual trauma and intimate partner violence place many women at increased risk of conditions like depression, anxiety, PTSD, and substance use.

Early recognition matters because symptoms tend to grow more entrenched over time if they are ignored or dismissed. Getting support sooner:

- Reduces the risk of crises and hospitalizations.

- Protects relationships, work, and physical health.

- Helps women feel less alone, less ashamed, and more in control of their recovery.

How Women’s Mental Health Differs

Mental health conditions do not appear in a vacuum; they are filtered through a woman’s body, roles, and environment.

Key biological influences include:

- Hormones and the menstrual cycle: Some women notice predictable mood changes, irritability, or emotional sensitivity in the days before a period.

- Pregnancy and postpartum: Shifts in hormones, sleep, identity, and responsibility can trigger or worsen depression, anxiety, OCD‑like symptoms, or trauma reactions.

- Perimenopause and menopause: Fluctuating estrogen can contribute to mood swings, sleep disruption, brain fog, and new or recurrent anxiety or depression.

Social and cultural pressures also play a major role:

- Caregiving roles: Women are often primary caregivers for children, partners, and aging parents, leaving limited space for their own needs.

- Gender‑based violence: Sexual harassment, assault, and domestic violence remain common and can have lifelong mental health consequences.

- Discrimination and stigma: Being labeled “too emotional” or “dramatic” can mean that very real symptoms are minimized by families, workplaces, and even professionals.

Intersectionality adds another layer. Risk and access to care are not the same for all women:

- Race and culture influence how symptoms are expressed, how safe it feels to seek help, and how clinicians respond.

- Sexual orientation and gender identity can influence exposure to family rejection, discrimination, and violence.

- Socioeconomic status shapes access to insurance, transportation, childcare, and time off work—all of which affect the ability to get consistent care.

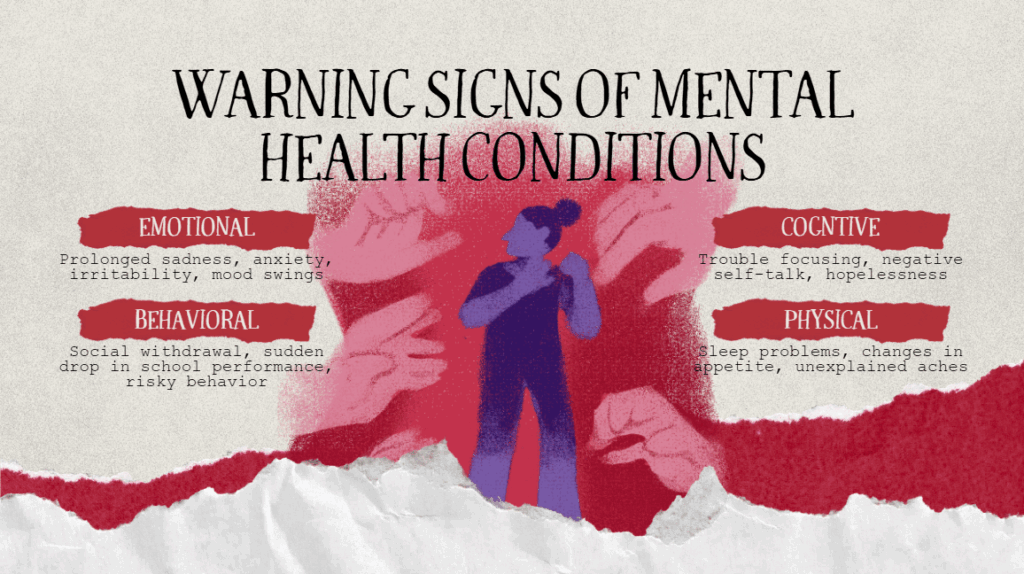

Common Signs and Symptoms in Women

Many women recognize something is “off” long before they are given a diagnosis. What they feel is real, even if they do not yet have the words for it.

Common emotional and mood signs include:

- Persistent sadness, emptiness, or tearfulness.

- Irritability, anger, or feeling “on edge” much of the time.

- Guilt, shame, or a harsh inner critic that will not quiet down.

- Emotional numbness or feeling disconnected from life.

- Mood swings that feel out of proportion to daily events.

Physical and behavioral signs can be just as important:

- Fatigue and low energy, even after rest.

- Changes in sleep (difficulty falling or staying asleep, or sleeping much more than usual).

- Changes in appetite or weight—eating much less or much more than usual.

- Overworking, perfectionism, or feeling unable to slow down.

- Withdrawing from friends and activities that once felt meaningful.

- Using alcohol, sedatives, or other substances to cope or to sleep.

Red‑flag symptoms signal the need for urgent or emergency help:

- Thoughts of self‑harm or suicide, especially if there is a plan or intent.

- Hearing or seeing things that others do not (hallucinations) or feeling detached from reality.

- Being unable to care for basic needs, children, or responsibilities.

- Being in immediate danger due to domestic or sexual violence.

Types of Mental Health Conditions in Women

Women experience many of the same mental health conditions as men, but the way these conditions develop, show up in daily life, and are recognized is often shaped by gender‑specific biological changes, social expectations, and lived experiences.

1. Mood and Anxiety‑related Conditions

Depression in Women

It can look like persistent low mood, hopelessness, irritability, emptiness, or feeling overwhelmed by everyday tasks. It can also present through physical symptoms like pain, fatigue, or sleep problems. (Internal link: Depression in Women)

Anxiety and Women

It may involve constant worry, restlessness, fear of something bad happening, or physical symptoms such as racing heart, shortness of breath, or stomach upset. (Internal link: Anxiety and Women)

Anxiety vs Depression

Although anxiety and depression often occur together, there are important differences:

- Anxiety tends to center on fear and worry about the future, often accompanied by muscle tension, racing thoughts, and a sense of dread.

- Depression is more focused on low mood, loss of interest, reduced energy, and a sense that nothing will ever improve.

In women, the two conditions frequently overlap. A woman might:

- Wake up with a heavy, depressed mood and go to bed with racing, anxious thoughts.

- Struggle to tell whether she is mostly “sad and drained” or “panicked and on edge.”

- Be told by others she is “just stressed” even though she is no longer enjoying life.

Getting the right diagnosis matters because:

- Different conditions can respond better to specific types of therapy and medications.

- Knowing whether anxiety, depression, or both are driving symptoms helps set realistic expectations for recovery.

- Clarifying the picture reduces self‑blame and confusion.

2. ADHD in Women

ADHD in women often involves challenges with attention, organization, time management, and emotional regulation, rather than obvious hyperactivity. (Internal link: ADHD in Women)

ADHD can look different in women compared with the classic stereotype:

- Inattentive type: Daydreaming, mental “fog,” difficulty following through, losing items, or missing details.

- Emotional dysregulation: Intense feelings, quick shifts from calm to overwhelmed, or strong sensitivity to rejection and criticism.

- Masking: Overpreparing, working late, or people‑pleasing to hide difficulties and avoid judgment.

3. Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

OCD is more than liking things neat or being “a little OCD.” It involves:

- Obsessions: Intrusive, unwanted thoughts, images, or urges that cause significant anxiety or distress.

- Compulsions: Repetitive behaviors or mental rituals done to reduce that distress or prevent a feared event.

Common obsessions and compulsions in women can include:

- Contamination and cleaning: Fear of germs or illness, leading to excessive washing or cleaning.

- Checking: Repeatedly checking locks, appliances, or the baby to prevent harm.

- Harm and responsibility: Intrusive images of hurting loved ones, even though the woman has no desire to do so.

- Relationship and moral obsessions: Constant doubt about being a “good enough” partner, mother, or person of faith.

- Perinatal/postpartum OCD: Disturbing thoughts or images about harming the baby, often accompanied by intense guilt and fear.

4. Trauma‑related and Stress Conditions

Trauma‑related conditions in women often stem from experiences such as:

- Sexual abuse or assault.

- Intimate partner violence, stalking, or coercive control.

- Birth trauma or traumatic medical procedures.

- Repeated exposure to threat, instability, or emotional abuse.

Post‑Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Complex PTSD can involve:

- Intrusive memories, flashbacks, or nightmares.

- Avoidance of reminders of the trauma.

- Hypervigilance, being easily startled, or feeling constantly “on guard.”

- Emotional numbing, disconnection, or difficulty feeling joy.

- Negative beliefs about self (“I’m broken,” “It was my fault”).

Common trauma responses in women also include:

- People‑pleasing or overaccommodating to stay safe.

- Difficulty setting boundaries or saying no.

- Staying in unsafe or unfulfilling relationships due to fear, financial dependence, or concern for children.

5. Perinatal and Reproductive‑related Conditions

Reproductive stages are critical windows for women’s mental health.

Perinatal mood and anxiety disorders (PMADs) include:

- Depression during pregnancy or after birth.

- Anxiety, panic, or intrusive thoughts related to the baby’s safety.

- Postpartum OCD, PTSD, or mixed presentations.

Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD) and severe PMS can involve:

- Significant mood swings, irritability, or despair in the luteal phase.

- Physical symptoms such as bloating, pain, and fatigue.

- Noticeable impairment in relationships, work, or self‑care during those days.

Mental health can also be strongly affected by:

- Infertility and fertility treatments.

- Pregnancy loss or stillbirth.

- Menopause, which may bring mood changes, sleep disruption, and shifts in identity and body image.

6. Eating and Body‑image‑related Conditions

Women are disproportionately affected by eating disorders such as:

- Anorexia nervosa: Severe restriction of food intake, intense fear of weight gain, and distorted body image.

- Bulimia nervosa: Cycles of binge eating followed by compensatory behaviors like vomiting, fasting, or excessive exercise.

- Binge‑eating disorder: Recurrent episodes of eating large amounts of food with a sense of loss of control, often followed by shame.

Social media, beauty standards, and cultural pressures can fuel:

- Constant body comparison and dissatisfaction.

- Pressure to be thin, toned, or “perfect” after childbirth.

- Beliefs that self‑worth depends on appearance.

Warning signs families and partners might notice:

- Dramatic changes in diet or rigid food rules.

- Avoiding meals with others or making excuses to skip eating.

- Frequent trips to the bathroom after meals.

- Obsessive exercise or distress if unable to work out.

- Rapid weight changes or health problems linked to nutrition.

Risk Factors and Protective Factors

Key risk factors for mental health conditions in women include:

- Family history of mental health or substance use disorders.

- History of trauma, especially sexual or interpersonal violence.

- Chronic stress (financial strain, caregiving burden, unsafe housing).

- Medical conditions and hormonal changes.

- Marginalization due to race, sexuality, disability, or immigration status.

Protective factors can buffer against these risks:

- Supportive, safe relationships and community.

- Healthy coping skills, problem‑solving, and emotional literacy.

- Access to affordable, culturally sensitive healthcare.

- Stable housing, employment, and legal protections.

Lifestyle also interacts with emotional health:

- Sleep: Irregular or insufficient sleep can worsen mood, anxiety, and attention.

- Nutrition: Skipping meals, restrictive diets, or high sugar intake can contribute to energy crashes and irritability.

- Movement: Regular, enjoyable movement supports stress regulation and body confidence.

- Stress‑reduction practices: Mindfulness, journaling, spiritual practices, and time in nature can all help.

Getting a Diagnosis: What to Expect

Consider a professional evaluation if:

- Symptoms last most days for more than two weeks.

- Daily functioning at work, school, or home is clearly affected.

- Coping strategies that used to work no longer help.

- There are any thoughts of self‑harm, suicide, or harming others.

During a psychiatric or psychological assessment, expect to discuss:

- Current symptoms, when they began, and how they affect life.

- Past mental health history and family mental health history.

- Medical conditions, medications, and substance use.

- Trauma experiences and reproductive history (pregnancy, loss, hormonal changes).

- Strengths, supports, and goals for treatment.

Sharing trauma history, reproductive history, and current medications is crucial because:

- It helps distinguish between different diagnoses with overlapping symptoms.

- Certain medications are better suited for specific conditions and life stages.

- Safety planning can be tailored if there is current or past abuse.

Treatment and Support Options

Treatment and support options for women’s mental health include therapy, medication, lifestyle changes, and community resources working together for recovery.

1. Medication Management

Psychiatric medications can:

- Reduce the intensity of symptoms like low mood, anxiety, intrusive thoughts, or impulsivity.

- Improve sleep, appetite, and concentration.

- Create more “room” to benefit from therapy and lifestyle changes.

Common concerns women have include:

- Side effects such as weight changes, sexual side effects, or emotional blunting.

- Fears about dependency or needing medication “forever.”

- Questions about safety in pregnancy, breastfeeding, or menopause.

Effective medication management is collaborative:

- The prescriber explains options, benefits, and risks clearly.

- The woman shares her values, preferences, and concerns.

- Follow‑up visits track response, adjust doses, and address side effects over time.

2. Talk Therapy and Counseling

Several therapy approaches are particularly helpful for women:

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Identifies and shifts unhelpful thought patterns and behaviors.

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT): Teaches skills for emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and healthier relationships.

- Trauma‑focused therapies and EMDR: Help process traumatic memories and reduce their emotional charge.

- Interpersonal Therapy: Focuses on relationships, roles, and life transitions.

Therapy supports:

- Developing coping skills that are sustainable in real life, not just on paper.

- Learning to set boundaries and say no without overwhelming guilt.

- Rebuilding self‑esteem and a more compassionate inner voice.

Different formats meet different needs:

- Individual therapy offers privacy and focused work on personal history and goals.

- Group therapy and support groups reduce isolation and provide shared understanding.

- Couples or family therapy can improve communication and support when relationships are affected.

3. Holistic and Lifestyle‑based Supports

Holistic supports do not replace treatment for moderate to severe conditions but meaningfully strengthen recovery:

- Sleep: Prioritizing a consistent sleep schedule and reducing late‑night screen time.

- Nutrition: Regular meals, hydration, and balanced nutrients to stabilize energy and mood.

- Movement: Gentle to moderate physical activity—walking, stretching, yoga, dancing—chosen for enjoyment rather than punishment.

- Stress‑reduction practices: Mindfulness, breathing exercises, body scans, journaling, and creative outlets.

Community and social support are part of healing:

- Peer support groups (in person or online) for conditions like postpartum depression, ADHD, trauma, or eating disorders.

- Faith communities or cultural groups that affirm a woman’s identity and values.

- Friendships where vulnerability and reciprocity are possible.

Integrating spiritual or cultural practices—prayer, rituals, traditional healing, or ancestral practices—can help many women feel more grounded and connected.

4. Telehealth and Virtual Care

Telehealth has expanded access to care by:

- Making appointments more feasible for women balancing work, caregiving, or chronic illness.

- Reducing travel time and transportation barriers.

- Offering greater privacy for those in small communities.

To prepare for an online session:

- Choose a private, safe space where you can speak freely.

- Test your device, camera, and internet connection.

- Have a list of current medications, symptoms, and questions ready.

In‑person care may be more appropriate when:

- There is significant safety risk or concern about self‑harm.

- A physical exam or certain tests are needed.

- Home is not a safe or private environment for telehealth.

How Loved Ones Can Help

Partners, family, and friends cannot “fix” a condition, but they can make a profound difference.

Practical ways to help include:

- Listening more than advising; validating that what she feels is real.

- Offering concrete help—meals, childcare, rides to appointments, help with paperwork.

- Learning about her condition so comments and expectations are more realistic.

- Checking in regularly rather than disappearing after the first conversation.

Things to avoid:

- Minimizing (“everyone’s stressed,” “just think positive”).

- Blaming (“you’re overreacting,” “you’re being selfish”).

- Threatening or using guilt as leverage to force treatment.

Encouraging treatment while respecting autonomy looks like:

- Expressing concern and care, not control.

- Sharing observations gently (“I’ve noticed you’re not yourself lately”).

- Offering to help find providers or go with her to an appointment, while leaving final decisions to her whenever safe to do so.

Crisis Planning and Safety

Recognizing a mental health crisis is essential. Warning signs can include:

- Active thoughts of self‑harm or suicide.

- Sudden, severe behavior changes or loss of touch with reality.

- Inability to care for basic needs or children.

- Immediate danger from another person.

A safety plan can include:

- Crisis and hotline numbers saved in the phone.

- Trusted contacts who agree to be reached in emergencies.

- Steps to reduce access to means of self‑harm (medications, weapons).

- Grounding or coping strategies that have helped in past crises.

For women experiencing domestic or sexual violence, safety planning may also cover:

- Safe places to go if leaving suddenly.

- Important documents, cash, and essentials kept where they can be quickly accessed.

- Codes or signals to alert friends or family discreetly.

When to Seek Professional Help

It is time to seek professional help when:

- Symptoms last most days for more than a couple of weeks.

- Daily life—work, parenting, relationships—is clearly suffering.

- Coping strategies like rest, talking to friends, or basic self‑care are no longer enough.

- There are any thoughts of self‑harm, suicide, or harming others.

Choosing between providers:

- Therapist (psychotherapist, counselor, psychologist): Focuses on talk therapy and coping skills.

- Psychiatrist or PMHNP (psychiatric nurse practitioner): Can diagnose and prescribe medications and often also provide therapy.

- Primary care provider: Can screen, start basic treatment, and refer to specialists.

Helpful questions to ask a potential provider:

- “What experience do you have working with women with my concerns?”

- “How do you usually approach treatment?”

- “How will we measure progress and adjust the plan if needed?”

- “How do you incorporate trauma history, culture, and identity into care?”

Turning Insight into Action

Turning insight into action starts with recognizing that what you’re feeling is real and deserves care. When you can name what is happening, you gain power to choose what happens next instead of staying stuck in survival mode. Even one small, intentional step toward support can begin to shift how you feel and how you move through your days. You do not have to wait until everything falls apart before you reach for help.

If you see yourself in these experiences and want focused, women‑centered care, EmpowHer Psychiatry and Wellness can walk that path with you. You do not need the “perfect words” or a polished story to get started—showing up as you are is enough. Together, you and your provider can clarify what you’re facing, explore treatment options that fit your life, and create a plan that feels realistic and compassionate. Whether you’re considering medication, therapy, or both, you deserve a safe, nonjudgmental space to heal. When you’re ready, reaching out to EmpowHer Psychiatry and Wellness can be the first concrete step in turning understanding into real, lasting change.